Adolescents are experimenting with electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and there is speculation that this might lead some young people who would not otherwise have smoked cigarettes to progress to smoking (the gateway effect). However, after ten years of experience in other countries where e-cigarettes are widely available, there is no evidence that this is happening. In fact, the opposite may be true, that e-cigarettes are actually diverting adolescents away from smoking.

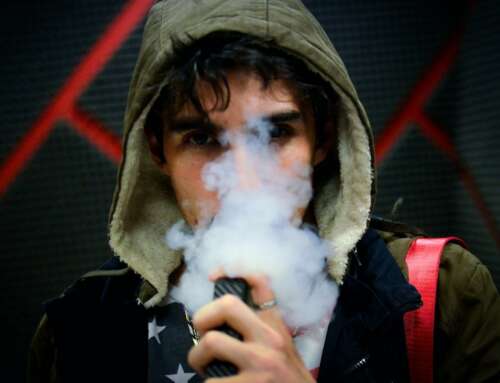

An e-cigarette is a battery-operated device which heats a liquid solution into a mist or aerosol that the user inhales, simulating a smoking experience. The mist usually, but not always, contains nicotine. E-cigarette use is known as ‘vaping’ and users are ‘vapers’. E-cigarettes have now been available in many countries since 2006 and much can be learnt from their experience.

Many studies have found that young people who use e-cigarettes are also more likely to smoke and some e-cigarette opponents have used this as evidence that vaping leads to smoking. 1, 2 However, this association tells us nothing about whether the vaping caused the smoking. A more likely explanation is that some young people are predisposed to experiment with both vaping and smoking (‘common causality’).

Importantly, regular e-cigarette use is almost exclusively confined to young people who already smoke.3, 4 It is rare for non-smoking youth to become regular e-cigarette users. In the UK, less than 0.2% of never-smoking youth vape regularly and there is no evidence of progression to smoking.3

Population trends also supports the lack of a gateway effect. As e-cigarette use by adolescents is rising, adolescent smoking rates are falling and are now at record lows in many countries. For example, in the US from 2013-2015 smoking rates dropped in 17-18 year olds at the fastest rate in 40 years (http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/data/15data/15cigtbl1.pdf). If a gateway mechanism is operating, an increase in smoking rates or at least a slowing of the falling rate would be expected.

One possible explanation for this reduction in adolescent smoking is that e-cigarettes are preventing smoking uptake. Young people who experiment with e-cigarettes may otherwise have smoked in the absence of e-cigarettes. Using an e-cigarette which may be more enjoyable and socially acceptable may prevent adoption of the more harmful behaviour. It is obviously better for young people not to use e-cigarettes, but vaping is preferable to smoking and is at least 95% safer.5

Further evidence to support this substitution hypothesis has emerged in US where some states have banned the sale of e-cigarettes to minors. Two large studies have found that the introduction of bans was associated with a significant increase in adolescent smoking rates compared to states without bans.6, 7 Banning e-cigarette sales to adolescents may be having the perverse consequence of eliminating a much less harmful substitute behaviour which is diverting users from smoking tobacco.

Furthermore, like adult smokers, some young people are using e-cigarettes to help them quit smoking.8 E-cigarette bans remove this therapeutic option.

Another argument claimed to support the gateway theory is that adolescents will become addicted to nicotine from e-cigarettes and then progress to a more potent nicotine delivery device, such as cigarettes. However, the great majority of adolescent e-cigarette users do not use nicotine. Only 20% report using nicotine in the US (https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future/overview-findings-2015/monitoring-future-figures-2015) and 28% in Canada.9

After ten years of real-world experience overseas there is no convincing evidence to support the notion that adolescent vaping leads to smoking. In fact, e-cigarettes may be a gateway out of smoking and may be reducing adolescent smoking rates.

– Colin Mendelsohn

Image from Unsplash

References

- 1. Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, Fine MJ, Sargent JD. Progression to Traditional Cigarette Smoking After Electronic Cigarette Use Among US Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):1018-23

- 2. Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG et al. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Initiation of Combustible Tobacco Product Smoking in Early Adolescence. Jama. 2015;314(7):700-7

- 3. Bauld L, MacKintosh AM, Ford A, McNeill A. E-Cigarette Uptake Amongst UK Youth: Experimentation, but Little or No Regular Use in Nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(1):102-3

- 4. Use of electronic cigarettes among children in Great Britain. Action on Smoking and Health, UK, 2015 Contract No.: Fact sheet 34. Available at http://www.ash.org.uk/information/facts-and-stats/fact-sheets(accessed June 2015)

- 5. McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Hitchman SC, Hajek P, McRobbie H. E-cigarettes: an evidence update. A report commissioned by Public Health England. PHE publications gateway number: 2015260 2015. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/e-cigarettes-an-evidence-update(accessed February 2016)

- 6. Friedman AS. How does electronic cigarette access affect adolescent smoking? J Health Econ. 2015;44:300-8

- 7. Pesko MF, Hughes JM, Faisal FS. The influence of electronic cigarette age purchasing restrictions on adolescent tobacco and marijuana use. Prev Med. 2016

- 8. Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):847-54

- 9. Hamilton HA, Ferrence R, Boak A et al. Ever Use of Nicotine and Nonnicotine Electronic Cigarettes Among High School Students in Ontario, Canada. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(10):1212-8

Leave A Comment