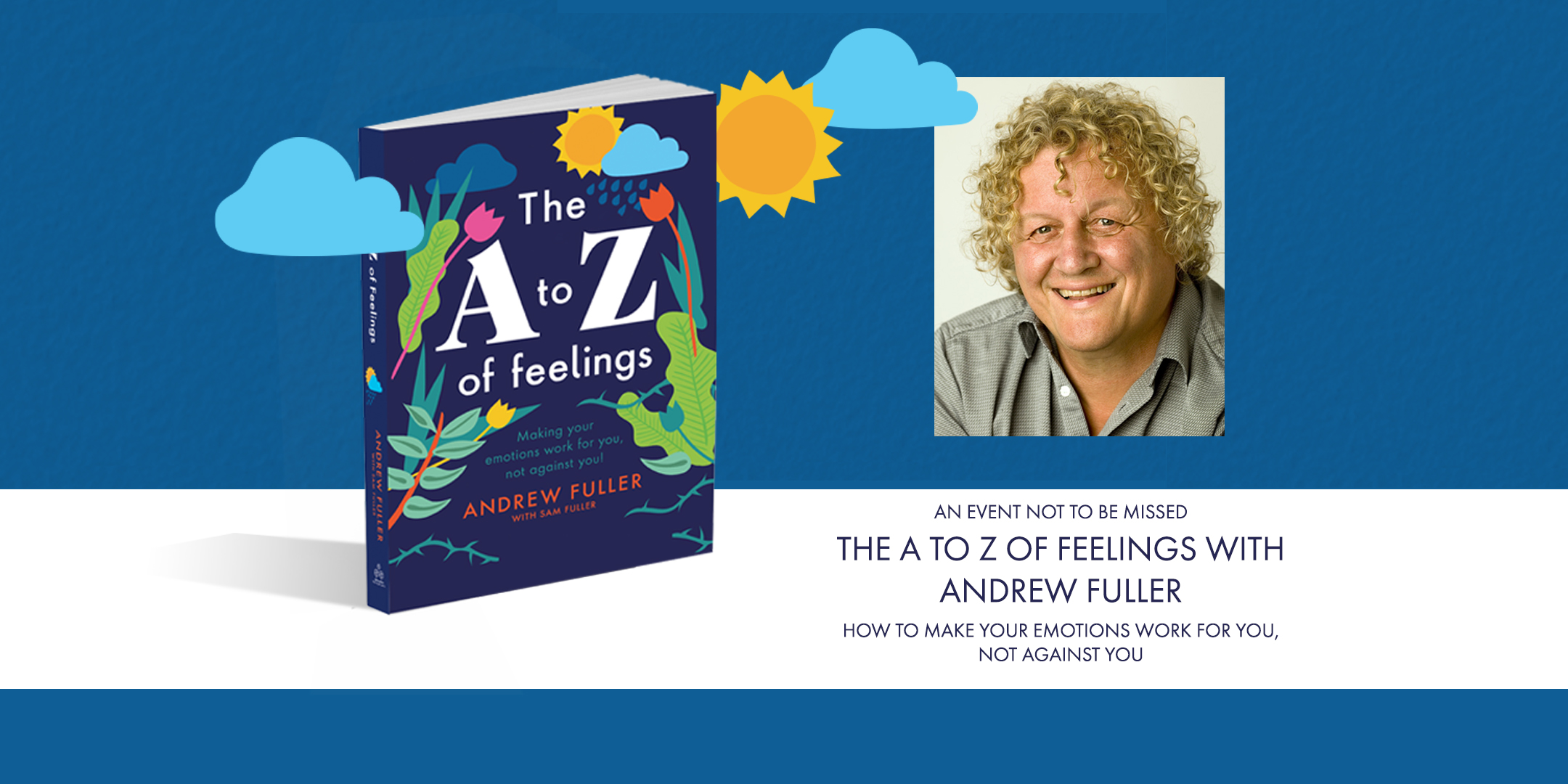

An extract from Andrew Fuller’s new book The A to Z of Feelings. Available May 2021 from Bad Apple Press

‘The rate at which a person can mature is directly proportional to the embarrassment he can tolerate.’

– Douglas Enqelbart

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes series of books, once sent a telegram as a joke to 12 friends that read, ‘Flee! All has been discovered.’ All the men were well respected in society. Apparently, Doyle was shocked to learn that within the next few days, all 12 men had left the country.

The Greek philosopher Sophocles remarked, ‘There is no witness so terrible, no accuser so powerful, as the conscience which dwells within us.’

What you may notice

Embarrassment is not a casual emotion, one you can shrug off and think, ‘So what, I’m embarrassed now.’ If you try to do this, you are likely to blush more vividly.

The feeling of embarrassment is linked to shame, social anxiety and guilt, but it is also a distinct emotion with unique physical signs played out on the body.

We might feel ashamed of our dancing skills and anxious about what others will say about our style of dancing, but also guilty because our partner loves to dance and we are reluctant to join in. To top it off, we can feel embarrassed that we have all of these feelings!

Complicating matters even further, we can feel just as embarrassed by being complimented or admired as by slipping and falling in public.

Embarrassment changes what people do. It is a powerful teacher. Most of us would travel a long way and complete a whole range of unpleasant tasks rather than repeating an act that is likely to give rise to this feeling. Embarrassment doesn’t bring about forgiveness; it creates avoidance.

Anyone who has mis-stepped and stumbled knows that ruse of trying to make it look purposeful in the hope that no one else notices.

Embarrassment lingers long. We don’t forget these moments easily.

Waking up after a night of alcohol-fuelled singing at a karaoke bar where you wowed the crowd with rendition on Sinatra’s ‘I did it my way’ will do it. Most people also know the dreadful realisation that comes when something they have done is cause for acute embarrassment. Embarrassment exists on a continuum from blushing to mortification and humiliation.

In some societies, embarrassment was equated with a loss of face and a dishonouring of one’s family. Sometimes it has been seen as worthy of exile or death.

Many of these features are seen in the modern cancel-culture where people are socially ostracised (the most painful form of bullying) for social misdemeanours.

Upsetting someone without intending to do so, asking for a possession to be returned or a salary to be raised can send some people into a squirming mass of embarrassed insecurity. Many people also dread difficult conversations not just because they lack conflict resolution skills, but they find them to be acutely embarrassing.

What happens

From having a guest enter your messy home to spilling drinks, having feelings of sexual desire and forgetting someone’s name and most bodily functions, we seem to find no end of things to be embarrassed about.

Hearing your own singing or speaking voice is enough to send some people into a spiral of self-consciousness. This is why the thought of public speaking (let alone public singing) mortifies so many people.

You don’t even need someone else to notice what you have done to feel embarrassed. Anyone who has ever dreamed they have shown up at work or school naked knows that embarrassment can occur even in our sleep!

The usual expression of embarrassment includes looking down, smiling or attempting to control or inhibit the smile. Embarrassed smiles differ from happy smiles. In a happy smile, the corners of the mouth up are pulled up and there is crinkling around the eyes. In the embarrassed smile, the lips turn up but the eyes don’t crinkle.

Typically, an embarrassed person will avoid eye contact, lower their chin, smile and then shift their gaze to the left. This is suggestive of right-hemisphere brain activation associated with withdrawal behaviours. People frequently touch their faces when embarrassed, or look away to the left.

Of course, the other key indicator of embarrassment is blushing. Some people blush when they are embarrassed and others feel embarrassed by blushing. Facial reddening can occur during other feelings as well. Blushing begins with a sharp increase in blood flow followed by a slower rise in facial temperature. The increase in blood flow is what causes the actual appearance of the blush. Other physical changes can include a rise in blood pressure and fluctuations in breathing.

Others are likely to detect our blushing well before we are aware of it ourselves. Beta-adrenergic receptors of the sympathetic nervous system appear to play some role in facial blushing.

Embarrassment and the brain

Although no one particular area of the brain has been identified as the site of embarrassment, there is a thumbsized bit of tissue located deep in the right hemisphere of the front part of the brain called the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, which is thought to be integral to the feeling of embarrassment. This region of the brain is responsible for regulating many automatic bodily functions such as sweating, heartbeat and breathing but is also linked to many thinking-related actions, such as reward-searching behaviours and decision-making. If the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex becomes damaged (as in people with

dementia), it can make people far less prone to feeling embarrassed.

What you can do that helps

It can be helpful to be aware of the three main functions of embarrassment.

First, embarrassment is a powerful social signal of appeasement. It is a sort of get-out-of-jail card. It is showing, ‘Don’t be too hard on me because you know I am giving myself a hard time about this.’ It also signals, ‘I am so sorry and I really, really, really didn’t mean it.’ It is clearly saying this mistake was not intended.

People who blush after committing a faux pas are viewed as more trustworthy than those who do not. Children who appear to be embarrassed by an action are less likely to be admonished by parents.

People often find it useful to confess that they are nervous and easily embarrassed before speaking to an audience. It often elicits kindness from the listeners.

Rather than hiding away feelings of embarrassment, learning to express them can help. Part of the reason we find the cartoon character Homer Simpson so loveable is his famous expression of frustration with himself: ‘D’oh!’

Secondly, embarrassment lingers long. We don’t forget these moments easily. We dread re-experiencing this feeling and avoid whatever behaviours triggered the state. Some excruciating episodes of embarrassment have caused people to serve longer sentences than many serious crimes. It is a form of social pain. Being aware that carrying past humiliations may be restricting your life is useful. Some past misdemeanours should have a use-by-date. Becoming kinder and more forgiving of yourself is needed.

Thirdly, embarrassment activates us to restore our esteem in the eyes of others. Find ways to get beyond the original event. Make amends if need be. Apologise to those that you may have hurt even if you never intended to do so. If that is not practical, devote yourself to a personal cause that helps victims to heal and recover.

Be aware that for some people, their sensitivity to embarrassment can be so strong they place their wellbeing at risk. Being able to say no, getting some medical check-ups, buying products that keep you safe and well are all essential. If you are squeamish and avoidant about doing any of these things, ask someone else to act as your guardian angel by reminding you how to overcome your embarrassment and to look after yourself.

To celebrate the launch of the A to Z of Feelings, Andrew Fuller will be holding a free webinar on Thursday May 27th, 2021 at 7pm AEST. Andrew will talk about the importance of understanding feelings and what they really tell us about our bodies and minds. Andrew will delve into the nitty gritty of what is going on in our brains when we experience emotions, and what they could be signalling about our lives. Hint: it is not always what you think! Find out more and register >>

Leave A Comment